I just submitted an article for a mission publication but its a bit long and boring and probably too academic so I thought I would just post it here.

It’s called “Being Human, Being Present” and it’s part of my reflections from The Nicholas Sessions last month in Prague.

BEING HUMAN. BEING PRESENT.

A priest in a pub discussing work conditions with steel workers. A monk who pitched his tent in the Sahara. A bohemian who started a community where Christians could be honest with each other.

Real stories.

Maybe I am getting older (please disagree) but I find myself increasingly fascinated by history and chasing down the stories behind the stories, the entrepreneurs who inspired the reports, the missionaries who dared to do church different whether they were noticed or not.

Real stories. Stories that made a difference.

We need these stories. We need “hopeful rumours”, a phrase I am taking from the revolutionary book, “The Prodigal Project: Journey into the Emerging Church” (2000) written by two Kiwis and an Aussie who described the new forms of church coming into our horizon at the turn of our century.

I remember seeing The Prodigal Project for the first time at the Greenbelt office in London where the freshly published book arrived in the post, it’s wrapping paper eagerly torn off by Greenbelt director Andy Thornton, a leader in the alternative worship movement. It was then I realised I was inside a story of global and historical importance, and my home country of New Zealand was not left out.

The term “emerging church”, although used for new church forms since the 1930’s, reappeared again in 2000 to capture what we were all seeing and the phrase stayed in our consciousness for almost a decade before others like “fresh expressions” supplanted it.

I have noticed that behind the commitment to new mission strategies (and catchy terms) lie numerous examples of creative risk-takers and innovators who tried something different to reach people untouched by existing mission efforts. These creative ventures were usually launched by pioneers, discovered by scouts, analysed by geeks, and articulated by church leaders who affirmed both the validity of the experiments and a daring “unorthodox” way forward for all.

At the Nicholas Sessions last month in Prague, a gathering for mission innovators to which I had the honour of participating, Bob and Mary Hopkins shared about the beginnings of what would later be named Fresh Expressions.

In their retelling of the story, I recognised the same players – the pioneers who created the stories, the number-crunchers who analysed the data (Lings, Wasdell, etc), and the permission-givers (Archbishops Carey and Williams) who put new phrases into currency and pointed ahead to a preferable future.

Another equally influential individual, in my experience, was a missionary statesmen who foresaw and recommended the shifts we now see on the ecclesiastic landscape. Canon Max Warren, General Secretary of CMS (then based in London), gave a deeply prophetic speech in Washington DC at the invitation of Overseas Mission Society of the Episcopal Church. The series of lectures was delivered in 1958 and appear in his book called Challenge and Response.

“The crucial question for the church is whether it is willing to take the risks of life on the frontier. If it does not do so, the time may come when it has nowhere else to live. For the fountains of the great deep are being broken up. We live in a world which is changing so rapidly that the demands on our adaptability, on our capacity for adjustment, are threatening not only to the ecclesiastical structures but also to the very stability of faith itself.” Max Warren, Lecture 4, “Re-minting of the world ‘Missionary’”, Challenge and Response, 1960.

Warren argued that the “home base is now one of the neediest fields calling for missionary work” and insisted that the inherited church structures were inadequate for ministry in a complex, modern, industrial world, We needed to allow new expressions of church to arise, new models that rise above territorial and diocesan limitations.

“The church anywhere and at every time is a mixed multitude . .. The church cannot be the organ of its own Mission. It must have organs of Mission. I would be ready to argue that a variety of organs are in fact indispensable, and under whatever different names they bear, do in fact exist wherever the Church is taking Mission seriously.”

Canon Warren did not live to see the current movement of “fresh expressions” or “mixed economy” that is now taken for granted in the Anglican world, but his words form a deep well of thought and permission-giving that has allowed his “mixed multitude” of church to become a reality, even in this age of post-modern, post-industrial challenges.

But even Warren needed concrete examples of church done differently. And here I want to point out three creative individuals who inspired Max Warren’s amazing challenge.

THE BLUE COLLAR PRIEST WHO TOOK CHURCH TO THE PEOPLE

“It is precisely this [pre-industrial church] structure that has come down to us almost without change, that has been left so woefully inadequate by industrialisation . . . Here, wholly new structures of engagement must be devised if there is to be dialog, influence and impact.” E.R. Wickham, Church and People in an Industrial City, 1957.

He dressed shabbily and hung out with factory workers at the pubs which was unusual for a priest back in the 1940’s. He might have been ignored if he didn’t later become Bishop. But he did. And the book that Bishop E.R.Wickham wrote, called “Church and People in an Industrial City” (1957), was probably the most influential source for Warren’s Lecture Number 4, not to mention it’s impact on Lambeth 1958. In his book, Wickham outlines the devastating chasm between the worker-class and those who dress up for Sunday worship and the resultant founding of the Industrial Mission in Sheffield in 1942 as an effort to break that barrier.

Wickham’s concrete examples of “supplementary non-pariochial structures” and social group thinking found a well-respected echo in Max Warren.

THE CREATIVE WHO STARTED A COMMUNITY

“Religion to me really is a song” Florence Allshorn.

Also in 1942, an artist named Florence Allshorn launched a revolutionary community in Sussex called St Julians. She called St Julians a place for all God’s children. It was a multi-national, ecumenical space for honest dialog and integral living.

She had already served a difficult term of mission service in Uganda with CMS in which she saw the danger of unaddressed, dysfunctional relationships among leadership on the field. She returned home bruised and, according to Eleanor Brown, ‘after a year in a curious little colony of “dropouts” in the Sussex countryside – a year of bohemian existence she found fascinating and freeing’ – Florence was ready to work again under CMS in England. She directed a small missionary training centre for women where she effected a “quiet revolution in the whole concept of missionary training,” focusing on in-depth honest relationships, love, and spiritual growth.

Despite having no official “She saw further than most into the meaning of missionary task”, noted missionary statesman J.H. Oldham who wrote a book on Florence and the community at St Julians. Canon Max Warren saw in this community the potential for a new way of doing church that went beyond idealism and conformity to the inherited pattern and towards

THE MONK WHO PITCHED A TENT IN THE SAHARA

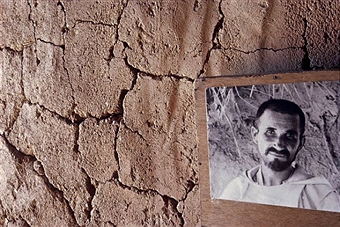

“Father de Foucault became a Touareg, to the depths of his soul. I mean that he completely gave himself to these people, not only spiritually but humanly; for he well knew how intimately the Christian life is bound up with the whole context of human life.” Voillaume, Seeds of the Desert.

The desert monk named Charles de Foucauld who went to the Sahara to found a monastic order died alone in 1916. No one joined him. But the spiritual journals he wrote had a profound effect on people as diverse as Dorothy Day (Catholic Workers), Thomas Merton (new monasticism), and even James Baxter (Jerusalem) in New Zealand. Some time after his death, The Little Brothers of Jesus came into being. Even today there are a dozen monastic orders named after him.

At the time of Warren’s lecture, a book called ‘Seeds of the Desert: the Legacy of Charles de Foucauld’ by R. Voillaume had been recently published and brought to the attention of clergy everywhere. Warren describes The Little Brothers of Jesus as a “daring new pattern of missionary service”, a way of interacting that was thoughtful, respectful (we might say post-colonial), open to dialogue, a strategy, according to Voillaume, of “being present amongst people, with a presence willed and intended as a witness of the love of Christ.”

Warren sums up, “What was so refreshing about [de Foucauld’s] plans, and what was so refreshing about Florence Allshorn, was that in their preoccupation with being present with God they were always so human. There was nothing stereotyped in the lives of either of these missionaries. Because they knew how to live “being present” with God”, they were able to live “being present” quite spontaneously with people of every kind and in every circumstance.”

Here we see the heart of Max Warren’s lecture that takes the challenge beyond the start-up of new church forms and beyond mere strategies into where it all starts: the challenge to live differently. To live more dangerously. To truly live among people, unprivileged people. To be open to openness. To allow ourselves to be overwhelmed by the full human experience and to participate fully in it.

This is incarnational missions the way Jesus showed us. “As the Father sent me, so I send you.”

Being human. Being present.

Thanx for writing the above.

Most a little strange to me. But hey, that’s not surprising, considering where I’ve come from and where I am at.

Lord, I want to be open to the many different ways in which you are working in our world today.